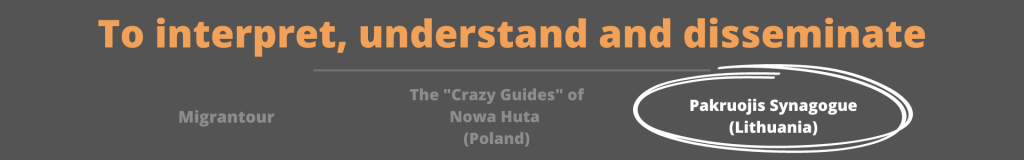

The Pakruojis Synagogue (Lithuania)

#11 Pakruojis is a small town in the north of Lithuania, mostly known for Pakruojis Manor and the Pakruojis Synagogue, two buildings with strong cultural and artistic importance. Although nowadays there is no Jewish community, in 1710 Jews settled in the town and for a long time they contributed to the economy and social life, becoming part of the village’s heritage. In particular, the Lithuanian Jewish Community owned the synagogue building but they left it abandoned and unsafe. After some years of talks, the building was sold to the municipality with a 99-year lease under only one condition; that it should not be used for business and only for cultural purposes. The acquisition of the property enabled the municipality to invest in the renovation of the building and create a full cultural design inside. The main motivation was to combat antisemitism and preserve Lithuanian Jewish cultural heritage for the next generations, making it more accessible to the public at the same time. After the building restoration, the municipality organized sessions with the local community to include them in the design of the new cultural offer: to combat antisemitism, restore heritage, increase the number of visitors, and address social problems by providing education and cultural opportunities. Several benefits came about. Firstly, although no specific study had been conducted previously, there seemed to be certain economic benefits for local entrepreneurs, such as restaurants and fast food outlets due to the increasing number of visitors. Moreover, thanks to this intervention from the Pakruojis municipality, the history of an extinct community has been recovered with the restoration of the building. The synagogue has become a place for education, aggregation and cultural encounter and now plays a crucial role in the socio-cultural development of the local community. The availability of financial resources granted by the EEA Norway Grant has been fundamental for the final result. In fact, preserving and restoring tangible cultural heritage is not only about renovating a building. It is about interpreting the complex socio-cultural values that a place carries from the past and giving them new functions in contemporary society, possibly balancing its value between the local community good and its potential as a tourism resource.