Storytelling Festival – Alden-Biesen (Belgium)

#8 Alden-Biesen lies in the eastern part of Limburg, a province in Flanders (Belgium). The environment is mostly rural and peaceful, attracting walking visitors and bike tourists. The Castle of Alden-Biesel (Vertelkasteel) is part of the cultural heritage of the area. Although it was built in its current form between the 16th and the 18th century, the castle actually dates back to the 11th century. Unfortunately, because of its border location, Alden-Biesel and its castle cannot easily be reached from Flanders. Accessibility is also limited. There is a train station in Bilzen, but the castle site is about 3 km from the town. For this reason, the main objective of the intervention was to promote the castle and make it feel more familiar to visitors, with an exciting cultural programming in the rooms inside. The focus chosen was education, targeting primarily schools, from kindergarten through to secondary schools and adult education. The most important activity that the castle organizes and that has become its brand image is the annual International Storytelling Festival. The festival started in 1996 and has become one of the biggest multilingual storytelling festivals in Europe thanks to the promotion of storytelling as an art and technique. It includes two events per year, one in January (for kindergarten and primary schools) and one in April (for high schools and adult education). What is special about the event is the fact that it is a pure storytelling festival: it is about the narrative, the spoken word, and the transmission of the unique artistic tradition of storytelling. It also addresses foreign languages, becoming the biggest multilingual storytelling festival in Europe. Over the years the castle has become a creative hub where imaginative people can meet and share knowledge with an enthusiastic audience in a wonderful historical setting. The impact of the event’s promotion is huge. The festival receives 12,000 visitors per year. Each of them generates an economic return and similarly, the art promoted by the storytelling leads to a cultural development for the whole region. The only drawback is the limited involvement of the local community, which of course can be improved easily in future editions. The importance of the intervention is that it teaches how rural areas are often rich in extraordinary, hidden pieces of cultural heritage. When used coherently and respectfully, they can provide unique opportunities to innovate the cultural offer of a region and position it in a specific niche of cultural tourism, thus improving its specificity and attractions.

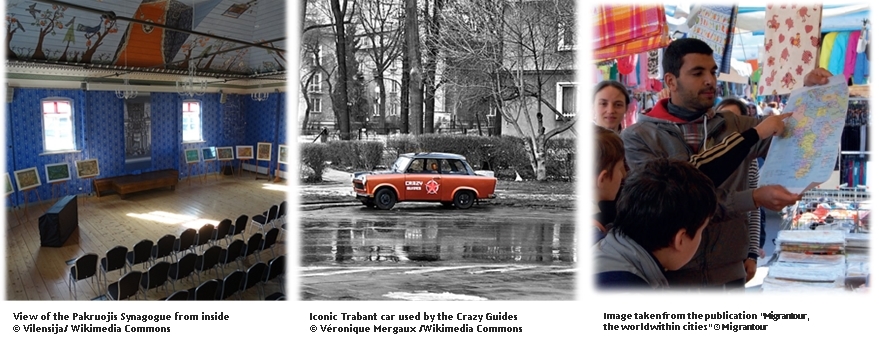

International Storytelling Festival event photo, Alden-Biesen (Belgium)